“Vote for only one.” It’s written on most ballots, on most races, between the name of the race and the names of the candidates. But why is a ballot with multiple filled bubbles void? And what is this “excellence” thing people do at Olin?

To start, the system used by the U.S. and most other national governments is plurality voting, a.k.a. “first-past-the-post”. In this nearly ubiquitous winner-take-all electoral system, each person gets one vote, and the candidate with the most votes wins.

Critics of plurality cite various negative mathematical and historical consequences of elections carried out in this fashion and generally hold up instant-runoff voting, a.k.a. “transferable voting”, as a fairer single-winner electoral system that is more conducive to healthy democracy—“the alternative vote”.

But is instant-runoff really better than plurality? Well, yes. But is instant-runoff really the best alternative to plurality? By most metrics, not really no.

Despite the fact that instant-runoff receives by far the most attention and discussion of all alternative electoral systems, there are numerous systems that are far better suited to choose our elected officials than either plurality or instant-runoff.

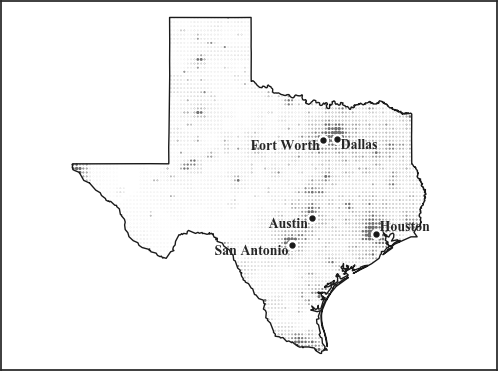

To aid in comparisons, let us distance ourselves from real politics and consider a vote for the new state capital of Texas. The five candidates are Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, Austin, and Houston. In this scenario, geographical location is an analogue for political alignment. That is, voters, distributed according to the real population distribution of Texas, will vote for the cities that are physically closest to them.

Figure 0. The map of Texas that will serve as the basis of this discussion.

It’s not immediately clear from looking at it which city is best to lead, so let’s hold an election.

With plurality, it’s straightforward. 23% of Texans vote for Dallas, 17% for Fort Worth, 23% for San Antonio, 10% for Austin, and 28% for Houston. Houston has the most votes, so it wins!

But wait. Is Houston really the best choice here? I mean, for one thing, 72% of Texans voted against it, among them the nontrivial western vote that sees this as the worst option.

For another, Dallas and Fort Worth are practically one city, and if they ran together, their combined voter base would be 40% of the population, enough to handily beat out Houston.

This is the spoiler effect: when two similar candidates run separately in a plurality election, split the vote, and lose where either of them could have won. The spoiler effect is the most commonly-cited flaw of plurality voting, and there are two common Band-Aid® solutions to it.

In the U.S., we have primaries. That means that similar candidates organize into parties, which then each choose a single nominee to run on behalf of all of them. In our example, Dallas and Fort Worth can team up as a single Northern Party. Taking the western vote, Fort Worth wins the nomination and goes on to the final.

Figure 1. The hypothetical party line with which our primaries operate.

However, in practice (as you may have noticed), such systems typically come to be dominated by exactly two parties. San Antonio, Austin, and Houston also team up as an opposing Southern Party. The South primary nominates Houston by the same pluralistic mechanisms as before. Then, Houston collects a 52–48% lead over Dallas and wins again.

This is kind of an improvement. At least now that we’ve seen the direct showdown between Fort Worth and Houston, we know why Dallas–Fort Worth didn’t win: given the choice between them and Houston, voters chose Houston.

It still wasn’t a very enfranchising election for western voters, though. Those in El Paso didn’t see anyone in the final election that they liked at all.

Beyond that, primaries are problematic for other reasons. They require voters to go to the polls twice each cycle—a biɡ ask for some—and they give immense power over our democracy to political parties, which it’s easy to forget are private organizations.

The other common solution is runoffs, a.k.a. “the two-round system”. An election governed by runoff voting starts off as an ordinary plurality election, but if no candidate earns a majority of the votes (or some other threshold), all but the top two candidates are removed and the ballot is run again (this is called the “runoff election”).

In our first scenario, the two top winners were Houston and, by a slim margin, San Antonio. In the runoff, San Antonio picks up western voters but, unable to win over Dallas and with a smaller core base, loses to Houston 58–42%. The final candidates were different, but the results were the same.

Western voters at least felt more enfranchised in the final election this time. That combined with the fact that runoff systems don’t automatically let political parties choose who ends up on the ballot makes runoffs solidly better than primaries. It still requires of voters multiple trips to the polls, though, and the result was still an eastern extremist.

Both of these issues are corrected by instant-runoff voting. Instant-runoff, as you might have guessed, is an expansion of the runoff system. It allows many runoffs to be virtually held while only requiring voters to ever go to the polls once per election. It does this through a ranked-choice ballot.

First, every voter ranks the candidates from best to worst. Then, a plurality election is held, with each voter’s vote taken as their top choice. If no candidate earns a majority of the vote (or, again, some different threshold), then the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. The votes that went to that candidate then go to the candidate that those voters ranked second. This repeats until one candidate has a majority of the votes.

Let’s return to Texas, and assume that each voter ranks the candidates from nearest to furthest. The first vote is the same as our plurality vote, then. The most votes one candidate has is Houston’s 28%, while the candidate with the fewest is Austin with 10%. Since Houston has no majority, Austin is eliminated.

Austin voters are divided four ways on whom they would choose next, with most turning to San Antonio. The new tallies come out to 23% for Dallas, 19% for Fort Worth, 30% for San Antonio, and 28% for Houston. Still no majority, so Fort Worth drops out next.

Unsurprisingly, Fort Worth voters mostly favor Dallas next, bringing it up to 40%. San Antonio’s number rises to 31%, and Houston remains at 28%. Having fallen behind, Houston becomes the final elimination.

Now this is the final showdown voters wanted to see. The two contenders represent a broad spectrum of geography, so while not everyone is completely satisfied, pretty much everyone has someone they at least like a little. Those who had voted for Houston are split, but most of them prefer San Antonio, handing it a 55–45% victory over Dallas.

The process is a clear improvement on plurality and its cousins. The spoiler effect is practically eliminated, as one of a pair of similar candidates will always be eliminated before the other. Because every voter is effectively consulted on every elimination (without requiring them to turn out multiple times), voters should feel more enfranchised, and the resulting candidate should better represent the whole of the population.

It’s still not the best answer, though. What if I told you that Austin, prior to its early elimination, had 49% of second choice votes? Or that San Antonio is actually farther from the average Texan than Houston? While instant-runoff is intuitive and spoiler-free, it’s far from mathematically sound.

A more advanced ranked-choice system is Condorcet voting. This is technically a family of electoral systems that includes Schultze, Ranked-pairs, Kemeny–Young, and others.

In a Condorcet election, the winner is the candidate who would beat every other candidate in a one-on-one election, if such a candidate exists. In the uncommon event that it doesn’t, the winner depends on which Condorcet algorithm is used.

Final tallies in Condorcet voting take the form of matrices: for each candidate i and for each candidate j, how many voters prefer candidate i over candidate j, or equivalently, by how many votes would candidate i beat candidate j? The answer is

| ⮟i, j⮞ | D. | F. W. | S. A. | A. | H. |

| D. | 0% | +2% | -9% | -20% | -5% |

| F. W. | -2% | 0% | -12% | -19% | -4% |

| S. A. | +9% | +12% | 0% | -54% | -17% |

| A. | +20% | +19% | +54% | 0% | +33% |

| H. | +5% | +4% | +17% | -33% | 0% |

The only city with no negatives in its row is Austin, so this time, Austin wins! At last, we have the one true capital of Texas. I didn’t want to spoil it earlier, but Austin is actually closer to the average Texan than any of the other contenders, so this is the best choice in my opinion.

So does this mean that Condorcet is the better “alternative vote” for which we’ve been looking?

Well, it still has its issues. Most importantly, it’s on the complicated side. It didn’t take as long for me to explain as instant-runoff, but expressing the final tallies did require tabular formatting.

Plus, there’s the question of what to do when there is no Condorcet winner. It’s very uncommon—I didn’t see it in any of the 51 simulations I ran—but it does happen. As I said, each algorithm has a way to select a candidate in that situation, but they’re all different, and most of them are themselves pretty complicated.

Then there’s Arrow’s theorem, which basically states that no ranked voting system can be both fair and logical, but that’s a whole discrete analysis rabbit hole I don’t want to fall into.

What if I told you that there was a third alternative about which almost no one talks that consistently achieves the same results as Condorcet, brings back the simplicity of plurality, and always has an unambiguous winner?

This is score voting, a.k.a. “range voting”, “point voting”, “evaluative voting”, “utilitarian voting”, “libertarian voting”, or “capitalism voting”. Score voting is simple and intuitive: each candidate is rated, say, from 0 to 10, and the candidate with the highest average score wins.

Running the Texas election again, we now assume each voter rates the candidates linearly by distance, normalized so that each voter gives at least one 0 and one 10. We now see Dallas get a 4.5/10, Fort Worth 4.4/10, San Antonio 3.8/10, Austin 5.5/10, and Houston 4.3/10. Austin wins again. Even though next to no one would place Austin as their first choice, it’s the one city that everyone can agree is a little bit better than average.

Despite the fact that score is way simpler than Condorcet, they usually get the same answer. In my simulations, whenever they disagreed, it was because score chose a smaller, slightly more central city. That results from the fact that score takes magnitude of voter preference into account while Condorcet knows only polarity.

Score is, in many ways, the ultimate electoral system. Still, there’s one last alternative about which I would like to talk: the special case of score voting where the fineness of the ratings is reduced to two levels, 0 and 1.

This is approval voting, or as we call it at Olin, excellence voting. Approval can be described as plurality with the one alteration that voters are free to vote for as many candidates as they like. The candidate with the most votes (the highest predicted approval rating) wins.

The points in approval’s favor are very different from those in score’s. In approval voting, voters can no longer express the magnitude with which they like or dislike candidates; only whether they approve or not. This reduction in information often leads to worse results.

In the case of Austin, its distance from the other major population centers is such that a handful of people like it a lot, and a lot of people dislike it a little bit. That’s what enabled it to rise above 5/10 last time. In approval, those preferences become pure likes and dislikes, pulling Austin down to 43% approval. The other cities, which polarized more evenly, fare similarly to as they did with score: Dallas gets 46%, For Worth 46%, San Antonio 34%, and Houston 39%. This time, Fort Worth wins by 0.1% over Dallas.

As I’ve stated before, Austin was, mathematically speaking, the best choice. It was preferred by voters over every other candidate when compared directly, and it was closer to the center of population than any other candidate.

But does it really matter? Fort Worth is actually only 7% farther from the average Texan than Austin, and, looking at the map, it’s not obvious that one is significantly better as a capital than the other.

I ran this simulation with all fifty states plus Washington D. C. (that one was pretty unexciting), and Texas was the only one that gave me four different results for seven different electoral systems. Most of them got the same capital no matter what was used.

That’s why, in spite of score voting’s mathematical superiority, I think that approval is the electoral system voting reformists should pursue. It’s a good enough improvement over plurality that can easily be expanded into full score voting later if public opinion favors it. Its similarity to plurality makes it more likely to catch on than instant-runoff or score, and it requires no modification to existing polling procedures beyond the removal of “Vote for only one” from the ballots.

But then again, there’s always [strong Arrow’s theorem](xkcd.com/1844).

In any case, happy voting this upcoming cycle, and remember: the other party is not the enemy. The Annunaki are.

Thanks to the Center for International Earth Science Information Network and the International Center of Tropical Agriculture for the population data I used.