The anonymous March 5 Frankly Speaking (FS) article, “Let’s Make Real Environmental Impact,” has me reflecting on what I had hoped to give when I came to Olin in 2018. Prior, I served as a professor for 27 years, the last 13 as the founding co-director of a center for sustainability in engineering. I learned many great and terrible lessons on my path to “have impact.” The first was that we will always have an impact; is it the impact that we want to have?

As I witness the divestment efforts unfolding I am moved to offer a few observations and learnings. I hope they are useful. My first observation is that Olin Climate Justice (OCJ) is cutting an admirable, textbook path of democratic action in service to social justice; I am awed by the high standard of scholarship in their communications that transparently grounds their case for divestment in data and explicit logics. Tyler’s March 9 email (subject: Olin Climate Justice’s Response to Board Statement) is another example. All would do well to follow their lead, it seems to me. A lesson I cannot forget is that I am part of the system that I long to change. The truth of anthropogenic climate change is that my actions are causal to the problem. It is not “someone else” who is to blame–it is me, yet I am not alone.

The March 5, FS article, if I understand it, is expressing a students’ sense of betrayal. It goes a little like this:

- OCJ communicates -> Author believes OCJ, presuming factual communication

- Board members communicate -> Author believes Board, presuming factual communication

- Board communications do not equal OCJ communications

- Author concludes OCJ communications are false

- Author feels betrayed by OCJ because of 4

All communications, as theorized by linguists Grinder and Brandler1, re-present the world in ways that delete, distort and generalize and therefore are neither factual nor true. I include the things I’m attempting to communicate now (and always, really). Our options are then to test what is said for its coherence with reality, investigate it, or have faith in the speaker. The “faith” option is frequently granted to those with perceived authority, but not always warranted.

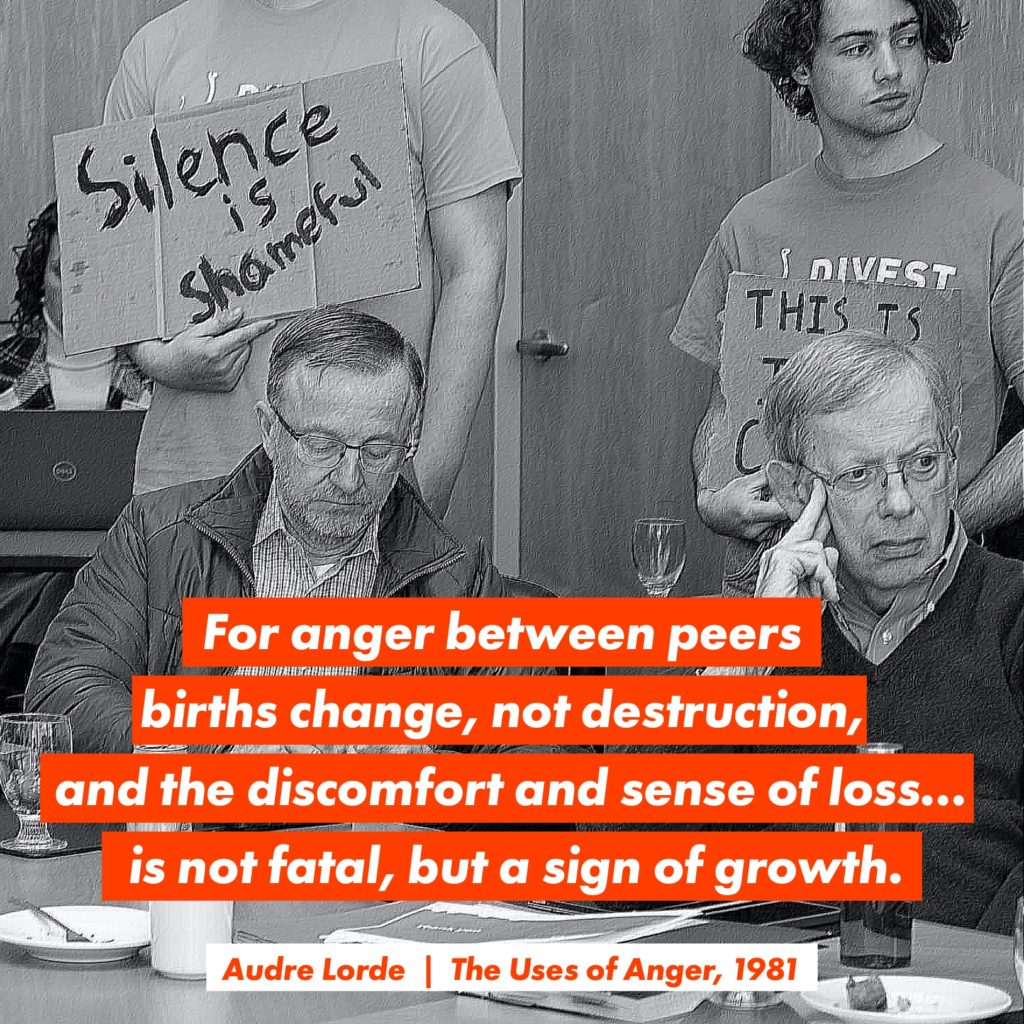

I have noticed at Olin that “collaboration” is often conflated with “consultation.” Collaboration is a mode of working that involves mutual respect and open power sharing. There are other properties but collaboration is distinct from consultation which is a mode in which one party holds power and exercises it unilaterally after seeking input from other parties (i,e., “consulting”); cooperation is another mode2. It is useful to recognize the distinction between these modes of working3. As the FS article points out, a dictate that another party adopt one’s point of view is not an act of collaboration–it is, as the biologist Humberto Maturana pointed out, a demand for obedience4. To be clear, the Board’s insistence that OCJ recognize what the Board believes to be a superior non-divestment approach is a demand for obedience; is it not an invitation to collaboration. The communication is this: If you only saw things the way I do, you would know I am right. That is, the assertion that OCJ was “non-collaborative” is a projection of the asserter’s state.

It is very tempting to relate to what is said as right or wrong. What is more likely is that the things said are both right and wrong or equivalently neither right nor wrong. For example, the claim that Environment Social Governance (ESG) is “more effective” than divestment requires all kinds of assumptions about the meaning of “effective.” Effective at what and for whom? Whose standard, shareholders’? How do stakeholders whose life, livelihood and future are stolen rate the “effectiveness”? In the end, I believe the dilemma of divestment must be addressed through authentic collaboration.

In my five years at Olin, I have witnessed cooperation many times, but I have only seen collaboration ~3 times. As I understand it, collaboration requires:

- A consciously-held, shared commitment to something larger than any of the party’s individual interests;

- A willingness for all parties to suspend their point of view for the sake of 1.

- A tolerance and patience with holding ambiguity long enough for a solution to emerge from the emptiness created by 2.

How do we access C? Usually through inquiry: A compels B and produces curiosity; this curiosity causes the parties to real-ize that their individual points of view are not as comprehensive as believed. In this realization, people relax their attachment, literally relax (somatically) and gain access to collective creativity. I have often found at Olin that if we get past B, the space for creativity in the social field (C) collapses. We cannot hold C–it is often said “we don’t have time,” but I think we mean that we don’t have courage.

At this, the end of my career, I have learned that all inequities, whatever form they take–environmental injustice, racial injustice, social injustice, organizational injustice, classroom injustice–are one thing: an abuse of power. The incredible beauty of the Olin community is that we long to do better. For this reason, I came to Olin. As I retire, my hope is that all of us would pursue a conscious awareness of how we wield power and ask, “Is it just?” We all want to live in a thriving world and we are the people we have been waiting for to bring it. I leave you with this quote from the 13-th century Persian poet Rumi:

“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing there is a field. I’ll meet you there.”