Below is an edited version of an essay I wrote during my Junior year of High School that pretty much explains why I decided to go to Olin. I hope it’s entertaining, and maybe evokes some reflection or thoughts or something.

—

The United States of America is huge, and the number of colleges within it is enormous. Because of this, high school students spend days, weeks, even months feeling stressed out and terrified of their futures. The process of preparing for college is extremely scary because as much as we can speculate about connecting the dots of our long-term plans for our futures, we really haven’t got a clue what the world will look like even a single year from now. When it comes down to it, college applicants should try to realize that their life will not be completely determined by the next four years.

That being said, no human can deny the human factor of fear. It is natural to feel fear of the unknown, and the future is exactly that. The idealistic solution to fearing the future is to think only of the present moment, which is virtually impossible in contemporary society, especially within our education system. Educational opportunity relies heavily on planning for the future. It is therefore impossible to avoid fear. Another possible solution to this fear is to rely on the assumption that any school that is a good fit for you will accept you and any school that rejects you did so because they would have been a bad fit. But there’s a problem with that idea too, because for everyone to get all of their needs met by one college, there would have to be an entire unique college for every student. There is no college that has it all, and there is no student who will be able to follow all their dreams in four years.

I am glad I finally made this realization because it convinced me not to rule out art school as a legitimate option for college. It all began in a crowded subway station under the streets of Brooklyn, NY. My mom and I visited four liberal arts colleges on the East coast over the past 3 days, and now we were headed to Pratt Institute, the first art college I would ever see.

“I think we get off here…” I mumbled, squinting at a map.

A man in a blue windbreaker and a baseball cap eyed us, obviously eavesdropping.

“Are you going to Pratt?” he asked.

“Yes, we are!”

“I’m headed there too. I can take you there” said the man.

“Wow thanks! Do you work there or something?”

“Yes, I’m the head of admissions”.

The A-train pulled up to the yellow line and my mom and I looked at each other quickly, our eyes wide with incredulity, before following the man through the automatic sliding doors of the train. For the next 2 hours, in the train and then in his cozy office at Pratt, Mr. Swan talked to us about the ups and downs of college education, fine arts in the contemporary world, and the importance of industrial design and engineering. He never once directly complimented Pratt or placed Pratt or arts education in general above any other kind of education. His last words were “Just remember that the next four years will not determine your life”.

I cannot honestly say I loved Pratt very much after going on a campus tour. I certainly was expecting more aesthetically pleasing buildings from an art college. But for my first perspective of an art school, the concept was heaven. A school of 4,000 motivated kids who, unlike an astonishing number of high school students, actually wanted to go to class and learn. The way I see it, you have to be pretty darn crazy to want to go to a prestigious art school so why would you be there if you aren’t passionate?

My biggest concern with art school is that they do not seem to recognize the importance of the integration of sciences, such as physics and chemistry, with art. For example, an industrial design major could design an elegant car, but without integrating science into their education, they won’t understand the physics that are necessary when considering aerodynamics and mileage, or the chemistry that could influence progress towards renewable fuels. It seems clear to me that many art degrees are simply incomplete without certain scientific knowledge.

Humanity is evolving as a species, and as a thinking society. New problems cannot be solved by art or science alone, and education must evolve accordingly… wait this is totally true but it’s a different point than the one I’m trying to make here… Here we go. Undergrad college is literally only 4% of your life, so if life leads you somewhere else, or you end up wanting to do something totally unrelated, or you just hate everything about it, you’ll be totally fine. It’s just part of your journey, it’s not an end, and stagnation is the worst thing a human can do anyways so just relax and do something that makes you happy.

Category Archives: 03 (March) 2018

The March 2018 Issue of Frankly Speaking

Never Out of Season Review

This is an apocalyptic nonfiction set in the present. Robert Dunn plaintively presents the problem of modern agriculture, and tells the story of the few scientists and projects hoping to save the world.

The problem, briefly:

We’re dependent, globally, on a few species of plants.

If any of them develops incurable pests or pathogens, society as we know it will likely die.

Key Takeaways

Dunn’s major point is that biodiversity is of critical importance. Basically, if one key crop species is infected or infested, unless we have already invested in finding alternative varietals of that crop (bananas, potatoes, rubber trees, coffee, cacao), we’ll experience massive global shortages, and the shortages might last indefinitely.

He argues with clear frustration that efforts to preserve and catalog biodiversity are underfunded and receive too little attention overall.

Like many environmental books, it’s written by a scientist who sounds scared and frustrated. Like most environmental authors, Dunn asks the reader to consider the long view. Rapid-producing monocultures mean short-term profit at the cost of global resilience.

Food Security

90% of nutrition globally comes from 15 species of plants.

Any given species of plant can be targeted by a pest, pathogen, fungus, etc. If that crop-killer works on one plant in a monoculture, it can take out the whole crop. The Irish Potato Famine is a prime example.

In order to produce the most product, most farms plant whatever one crop species creates the highest yield. Basically, biodiversity is disincentivized, because planting something other than the highest-yielding species is like throwing away money.

Modern Materials

Rubber comes from rubber trees, primarily in Southeast Asia, usually planted close together.

Brazil has had rubber tree plantations, but there is a pathogen there that attacks rubber trees. If that pathogen reaches Southeast Asia, rubber on Earth will become a scarce resource within a year.

There are a lot of stories like this in the book, making the point again and again that our situation is precarious.

If something starts killing one of our major crop species, pandemic is likely, and we don’t have alternatives at the ready.

Dunn also cites a decline in public funding for the study of crop diversity, insects, and pathogens. We have some seed banks, but not a lot of libraries, databases, or staffed laboratories. The situation is worsening rather than improving.

What can we do?

In Michael Pollan’s New York Times essay “Why Bother?”, he relates his reaction of letdown and disbelief at the end of “An Inconvenient Truth”, when the viewer is asked to contribute by changing lightbulbs:

“The immense disproportion between the magnitude of the problem Gore had described and the puniness of what he was asking us to do about it was enough to sink your heart.”

Dunn’s book has the same disproportionately small ask. Like Pollan, he advises the reader to plant a garden– then participate in adding to our digital databases through citizen science:

Citizen Science Projects

Plant Village is a database and forum for the sharing of crop health information.

Students Discover is a set of lesson plans for kids to track plants, pests, and pollinators in backyards and schoolyards.

Citizen science is cool; cataloguing bugs and plants is a genuine contribution to the field of biodiversity.

Is that all?

The real ask is implicit– here’s what Dunn is not asking:

Create political pressure to increase funding for studies of biodiversity. At a town hall, I asked my representative why climate change was not on her slate of priorities. She told me frankly that she doesn’t hear about it much from constituents. If you want your representative to represent you, tell them what you need!

Make plant genetics or pathogen study into your passion and crusade– become a researcher. Dunn points out that there are fewer than ten specialists globally for each of several major food crop types. So, one more researcher can have a huge impact.

However, assuming you’re not up for a major lifestyle change, an account on iNaturalist is a nice way to turn nature walks into scientific data collection expeditions! There is a shortage of data, so citizen science really is worthwhile for this application.

Imposter Syndrome

Singapore!

Talk to anyone who studied at NUS (National University of Singapore) and you’ll soon see why Singapore has all the right ingredients for a memorable study away experience. From academic excellence to cultural diversity, it’s no wonder that over a dozen Olin students have studied in Singapore at NUS. It explains why NUS students want to come to Boston and study at Olin – we have so much in common!

Singapore is as a global commerce, finance, transport and education hub and considered the most ‘technology-ready’ nation by the World Economic Forum. Singapore has a unique blend of the East and the West, the old and the new: it is clean, has great roads, transportation, airports, and a cosmopolitan life. Yet the basic eastern values and culture are also evident in the lifestyle of the people who inhabit this small island city-state in Southeast Asia. The blending of so many cultures (Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian) offers a unique worldview for both residents and visiting students and scholars.

The multicultural population of Singapore is well known for its friendliness. Students from the US quickly acclimate to life here thanks to the prevalence of English — spoken by a full 75 percent of its population. In fact, English is Singapore’s official educational language. Besides being a diverse and beautiful place to study, it is also extremely safe. Singapore has strict drug laws which has resulted in very low crime rates. The city streets are clean and secure as is the public transportation system. Singapore is second only to Tokyo for the World’s Safest Cities according to TripAdvisor.

Singapore is also known as the city that never sleeps. The city is alive with people and activities throughout the day and well into evening. Night owls in particular will love life here, where shops, restaurants and other attractions remain open way into the wee hours. NUS exchange student Hong Giap Tee speaks highly of the fusion of local cultures in Singapore’s cuisine, and recommends that visiting students experience it. If you decide to study at NUS, the school pairs international and exchange students with local students who can introduce you to many aspects of the cultural life of Singapore, including delicious Singaporean fare!

If you’d like to learn more about Singapore, let us know and we can connect you with our Global Ambassadors (students who have lived or studied in Singapore). If you want to explore a semester abroad at NUS, email studyaway@olin.edu.

Solar-powered ‘supertrees’ in the Gardens by the Bay in a world-class nature park in Singapore

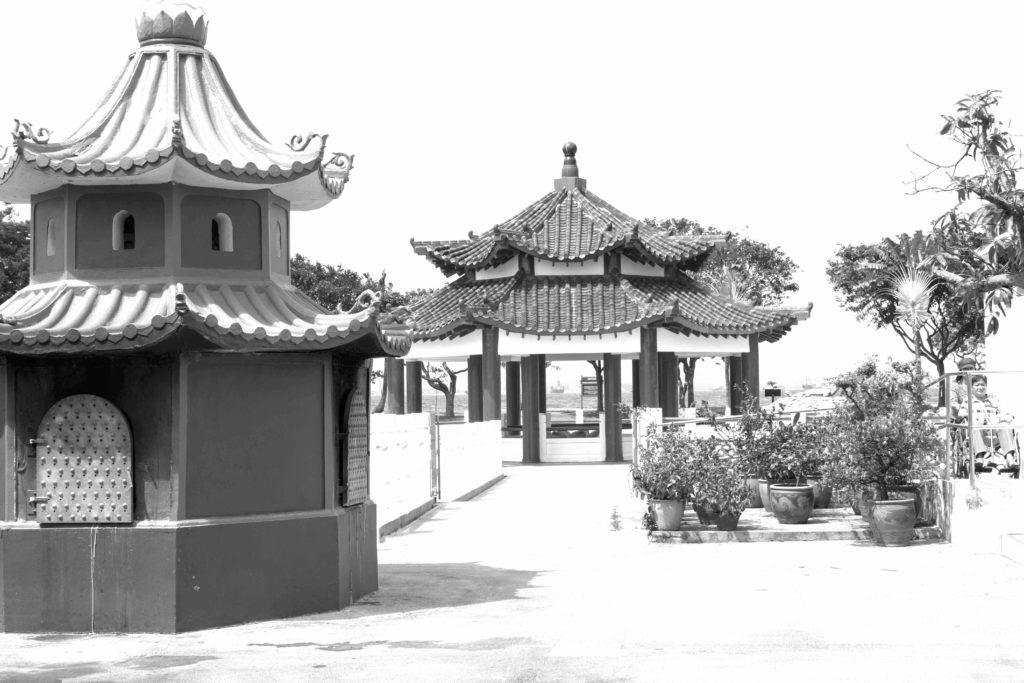

This temple is located on one of the off-shore Islands surrounding Singapore. Some of the islands feel as though you travelled 30-40 years into the past.