This study began with a simple question: if a person thinks that they are not doing well in a class because they are not putting in as much effort as they should be, would that person be more or less inclined to notice the faults in the class and give feedback?

Okay, maybe not that question exactly. The original idea was not as scientifically eloquent, and it derived from a conversation I had about how we develop a sense of control over our lives. For example, if I do not do well on something, no matter how difficult the challenge is, I see it as a personal fault. I tent to shrug off comments like “that class is hard” or “the workload is absurd” as irrelevant – if I do not do “well,” then it is still my fault. I just have to do better. With this in mind, I began to realize that I generally do not give very detailed feedback on my classes (tsk tsk, I know…), because I can never think of how the class could improve; I can only think of how I could have done better in it.

Thus, out of my own curiosity, I posed two questions to the Olin student body:

1. If you are in a class, and not doing well, do you blame yourself or do you blame the class?

2. How likely are you to give feedback for improving a class?

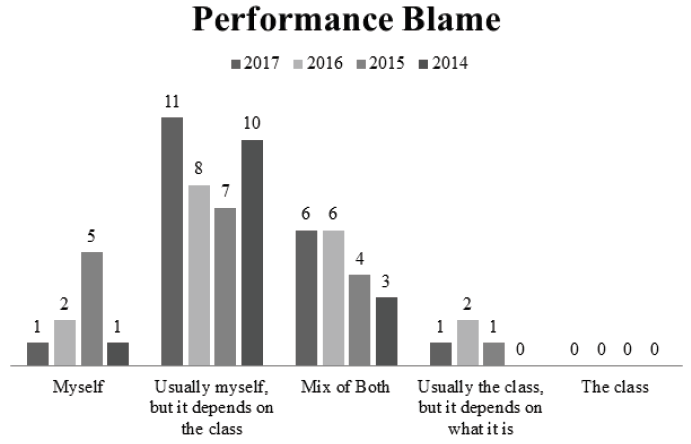

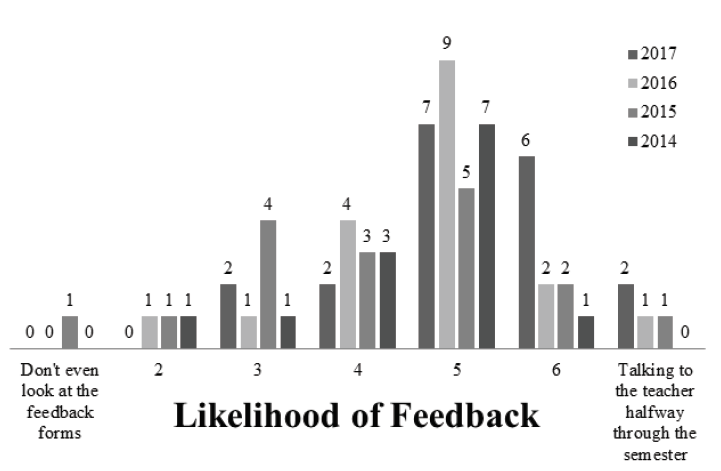

Please note, I use the term “blame” loosely. The sample size of the results was 67 students, about 15-19 (~20-25%) per year. The scales, as shown in the corresponding figures, I admit were a bit ambiguous. However, the results differed from my expectations. I did not see any correlation between individual’s responses to the two questions at all. Distribution was fairly even across the board, no matter the year – it was just as likely that a person would answer low on the scale for #1 and high for #2, as it was for a person to answer high on #1 and low on #2.

For class performance blame (question #2), the majority noted that it often depended on the class (eg. some classes are just blatantly harder than others, or receive routine bashing either way), but otherwise they were more inclined to blame themselves for not doing well. The most common excuses provided for doing poorly were disinterest in the class, an existing personal short coming, or taking a lot of credits. It was also noted that some gauge how well they are doing based on their peers. If everyone is struggling, it is more likely that the class rather than the individual is at fault. Those who placed more blame on the class stated that the classes they do not do as well in are those that are poorly structured.

In terms of feedback (question #2), there was almost a universal idea that it depended on the feedback culture, but most people strive to give what they can. I also learned that solicited feedback is more likely to get responses, and feedback discussions earlier in the year make feedback seem more welcome and open. If feedback is not solicited and it is late in the year, students often feel that feedback is unwelcome, especially if a lot of people are not doing well. There is also, unfortunately, a fear that giving negative feedback may anger the professor and result in punishment of the student(s). This is practically unheard of at Olin, so don’t be afraid to give your professors positive or negative constructive feedback at any point.

Feedback is incredibly important at Olin, and we pride ourselves on our outstanding feedback culture. Don’t forget to fill our your course evaluation surveys on my.olin.edu, and talk to your professors if you have anything else to add.