I tell people I hate all project teams — so they quizzically ask me why I am on two of them. The reality is I don’t hate them in the strongest sense of the word; rather, the argument is too long to explain, so I keep it short and life goes on. I’ve fleshed it out over time, conversation upon conversation I’ve reached an equilibrium where I feel like my beliefs are grounded enough to put into writing. And after so long, I’m writing this manifesto as a record of my current stance. In short, I think that Olin’s project teams do not do enough to benefit the student population and college at large because they are run like mature corporations, so we need to reflect on ways to return to a start-up mentality.

Project teams suffer from a value cap. What I mean by this is that beyond a certain time spent per week, the value that a member experiences from a project team diminishes greatly. I believe that value can be derived from happiness stemming from altruistic endeavors, pride in one’s work, pure academic learning, and many more. Beyond this cap, the member experiences no further benefits at the cost of time. You probably don’t realize that it exists — you work until your work has reached a good place and then you time out — it feels normal. Just like a 9-5, you put in the effort to reach the goal and then you’re done. At Olin, this cap is too low across the board on all project teams. During high school, I spent 18 hours a week on my school’s project team and not a moment of it felt like a chore. Now, the two project teams I am on combined barely scratch half that and I watch the clock like a hawk. Maybe you don’t feel it yet — a young, idealistic first-year with so much to learn and so many opportunities and obviously that FRC experience under your belt — but as your time at Olin progresses, this cap will get lower and lower. You wonder why all project teams are so youthful: first-years, sophomores, where are the upperclassmen? The fact that Olin project teams have become accustomed to the trickle-down of leadership to underclassmen is a symptom of the value cap leading to the disengagement of senior members. Upperclassmen realized a long time ago that the machine would keep churning with or without them, so they made their escape before being turned into soulless pulp.

The cap has a perfectly predictable lowering over the course of a student’s time at Olin. At some point, learning stagnates — an avionics programmer can only learn so much C++, a structures member can only perfect a composites layup so much, a drivetrain engineer can only engineer so many drivetrains, and an ECE who took ECE courses finds that their skills have surpassed any potential learnings of being on a project team (applies to any major). We are fighting against this natural process and we are losing. Olin’s project teams need to find a way to raise the cap so that any student with any time commitment can still find value in one more hour.

In terms of value, for the unnamed project teams I reference, altruism is not on the table. This leaves one thing. The only thing that Olin project teams hold on to. Pride. Yet, somehow, they managed to rot even pride from the inside. They asked first-years to redesign that part that had been redesigned the year before and the year before and the year before in the exact same way because that legacy design was fully functional to begin with. They actively pushed for this, laughing off the ones who wanted to attempt it for themselves first. They told them, this is how it was done before, this is how it is done, and this is how it will be done. And the impressionable first-year thought nothing of it. They are more experienced, having taken more classes and done the exact same thing the year before, they know exactly how to avoid failure. They took changing competition goals, requiring a completely reworked design to perform well at competition, and blurred the lines until a high-wing monoplane careened down the runway for the innumerable year in a row, because that’s all that they knew. When projects are underwhelming it is nigh on impossible to feel pride.

Failure. It’s a word often thrown around in idioms and half-assed wisdom from big tech CEOs on 30 Under 30. It’s painted as the Holy Grail of learning and ironically rightfully so, despite its cliché nature. Yet, Olin project teams wiped that line from their programming. There is no project team willing to try something unique or unproven on accounts of it increasing their failure chance. There is no attempt to experiment for the sake of learning. The forefathers had functional designs; replicate, replicate, replicate. In high school, I spent $2,000 of my own savings on my project team and the results were disastrous. I watched planes nosedive into the ground at terrifying speeds, planes disassemble midair and become lodged at the tops of 100 ft trees, landings that should’ve been classified as debris fields, and many more. I sacrificed my time, my savings, and my emotional health seeking the high of success. And on completing that goal the spring of my senior year, an autonomous search-and-rescue unmanned aerial vehicle, the future wasn’t as bright as I’d hoped. As the wheels touched down for landing after the maiden flight, I realized that the journey was over. All the things that I had learned had come before when the planes were not successful, when we tried new things for the sake of trying them, because we had nobody to teach us — but now we hadn’t crashed.

As my freshman year of college passed, I watched my highschool team fall into the project team trap. From when I was on it with eight active members, having built three massive planes my senior year to have two of them be destroyed, they had only regressed. They built no new planes the whole year, instead focusing on modifying the wing airfoil of the legacy I’d left and building PCBs to replace the spaghetti wiring. But they profited — none of them had to spend a dime of their money and recruitment pulled in swarms of new members, surpassing even Olin’s most crowded interest meetings. Everyone wanted a piece of that success. And next year with the same competition and the same general goals, it will repeat itself, climbing ever higher on the rankings towards the perfection they strive to achieve. They should be able to see that this isn’t the fate forced upon them — they build wings with plywood and laminating film, something that could be transitioned to carbon fiber composites, yet they haven’t innovated. There’s room to learn there and grow, but after that? There’s nothing in the book after a fixed-wing monoplane made of carbon fiber: only blank pages. And throughout this whole ordeal there will be no significant failure; learning is greatly diminished. I hope you see the parallels at Olin and the difference in value cap between when I was on my high school’s project team and after I left it. One was worth $2,000 and 18- hour weeks, and the other clearly not. They fell into a trap of hyperfixations, working on small improvements and holding on to past successes. This is the trap of success.

You could say that my highschool team had moved from its start-up phase into the corporate world. Rather than having the ability to be nimble and allow failure, they had come to the harsh reality that they had expectations to uphold. Failure is hard to swallow in the eyes of project teams — not going to competition or not placing well means that members will foolishly leave and sponsors will too. I will let you young engineers in on a little corporate secret. Psst, failure is not permissible in the corporate world. A recall can lead to millions in losses, a mis-dimensioned part could cost millions for reconfiguring the assembly line, and negative customer perspectives mean millions lost in future sales. Welcome to Nissan, Boeing, Google, etc. Now is the time in a young engineer’s life to experience liberty and failure, and Olin project teams are failing the students at being that sandbox for creativity.

So far, I’ve outlined a circular problem, which I will reiterate here. Olin teams are run like corporations and as such fail the creative genius of young engineers at Olin. They do this to maintain a high level of security against failure and thereby protect member yields and sponsors. The more they have on the line to lose, the more aggressively they protect it. In this manner we arrive at a Catch-22, which I will break down further in a bit. I would first like to discuss two more factors of project teams that complicate things further: competitions and careers.

Competitions are parasitic. They pose one of the largest drains on project team budgets, are a huge waste of time since most of the competition is sitting around doing nothing, and are the only obvious way of staying relevant to sponsors and prospective members. In return, competitions provide rules and goals, both of which can be detrimental to project teams. Rules can stifle creativity and limit the freedom of project teams to do anything except churn out replica deliverables. Goals, which normally are stagnant (except in some rare cases of competitions changing goals each season), lead to the never-ending design cycle of rinse and repeat. Both of these downsides have been discussed in great depth previously regarding project teams, but it is important to note how they originate both from within the teams and outside them. In the end, it is up to the team to make the most of these constraints and be creative, but we don’t see any examples of that.

Finally, I believe that project teams are a necessary evil. Olin pumps out a high percentage of engineers that go straight into the workforce. These engineers wish to get internships and jobs and as a result feel compelled to do at least one project team for the infamous résumé. It’s on every job/internship listing, “project teams or real world experience required.” And honestly no wonder recruiters consider a project team real world experience; it’s f***ing corporate! This is the career dilemma.

Now, we reach the ineloquent point where I need to tie together loose ends, propose solutions, and write a call to action. I will admit that while these problems are apparent to me and indubitably, ubiquitously exist, the solutions are not so. I believe that the steps to remedy this require a rethinking of the role of project teams in Olin’s community, a reflection on the value of competitions, and a change in how Olin supports new teams.

A project team is truly only a valiant endeavor in its first 2-3 years after inception. This time period is marked by there being no legacy work to copy, many failures, and altogether a huge emphasis on experimentation and iteration. Beyond this time period, a project team’s future is at the hands of its leadership. Although a project team can try to sow liberty and freedom and promote failure as permissible, unless it parts from its legacy goals, it remains entrenched so deep that it succumbs to the chronic condition I’ve outlined. A well-managed project team, when reaching maturity, will pivot its goals greatly in order to start a novel project from the ground up. This could be one of three things: moving to a new competition bracket/goal, pursuing a new competition altogether, or abandoning competition entirely.

Those three aforementioned options are in order of difficulty. The first two maintain the grandiosity associated with competition and the sponsors and member recruitment opportunities. As a result, they also are the least likely to remedy the problem. A team with replicatory ideals will attempt to apply the same strategies to whatever new goals come their way unless it is a failing strategy. A rocket with a goal of 10,000 feet and a rocket that reaches 30,000 feet can be made using the same techniques — it’s only a question of scale. However, a liquid fuel rocket and a solid fuel rocket differ entirely. Shrewd leadership is a necessary corrective force for steering a project team away from copycat strategies.

A project team that gives up on competitions altogether will reap the greatest rewards, but face the toughest challenges. The most apparent is the pecuniary struggle in which the team finds itself. This can be remedied through proper fundraising, focusing on the value that the team brings, rather than competition rankings. The second, and arguably larger, hurdle is that of misdirection. A team without a competition is a team without a goal, unless a strong leadership steps in and inspires the team with one. This involves not only the goal itself, but rigid deadlines, and firm stakeholders that ensure that the team continues operating with some amount of direction and reasonable tempo.

And in the most extreme case, we must let the team perish. Pivot or perish — this is not corporate — we don’t aim to persist. Olin is founded on principles of adaptation and innovation; ingrained in our culture is the idea of avoiding the traps of stagnation. We preach to reevaluate everything and redesign our courses, our culture, and systems whenever and however necessary. Why should project teams escape this cycle? The project teams I envision, let’s call them neo-project teams, embody a start-up’s ephemerality, but unfortunately Olin is not prepared to handle these types of organizations. There are major roadblocks in securing space and money, barring new project teams from entering the arena.

In an ideal world, neo-project teams would be highly successful, dramatically raising the value cap, enthralling the attention of Oliners, and each delivering value surpassing that of all of today’s project teams combined. The composition of neo-project teams would become almost uniform, with each year making up a quarter of a project team’s membership and leadership being delegated to seniors at the higher level and juniors at the lower level. Oliners would find the time to be on only one project team and would pick that work over the alternative of 20-crediting or splitting their efforts across many. These are the signs of a thriving team. Neo-project teams would sow creativity, autonomy, confidence, and promote learning through failure.

I would like to end by breaking the fourth wall with you, the reader. I don’t believe that my analysis in this manifesto was exhaustive — you may have identified other problems or believe in different solutions. That is fine; what is important is that we talk about this, not suffer in silence. The responsibility now falls upon you to continue this discussion, ensure that your project teams don’t fall into complacency, and unite our community so that together we can prevent the Tragedy of the Project Team.

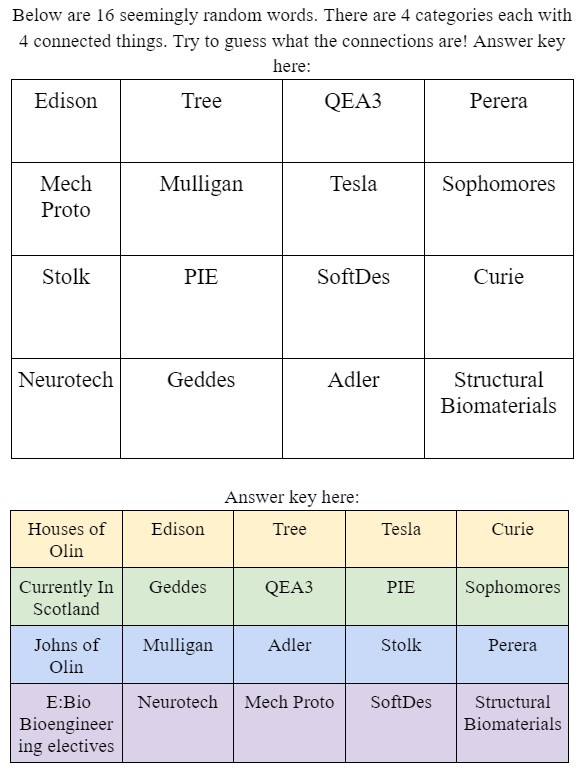

Category Archives: 10 (October) 2023

OPEN Review: Nimona

Dear Olin Community,

I am proud to announce the beginning of a new tradition, the connecting of minds and hearts through books, movies, podcasts, and any other media you can think of that contains flavors of LGBT+ characters and concepts.

For our debut, I will be reviewing the Netflix feature film Nimona. If you haven’t checked this movie out, I implore you to give it a try.

Plot summary (without spoilers):

Ballister Boldheart is a knight in a futuristic medieval kingdom who’s fought tooth and nail to earn his place among the noblemen that share his ranks. He has been met with critique and skepticism throughout his life due to his lack of high-esteemed family, but that has only made him more determined to succeed. When he is suddenly outcast due to a crime he’s falsely accused of committing, he must team up with a witty, chaotic kid named Nimona to find a way to clear his name. Little does Ballister know, Nimona turns out to be the exact type of creature he’s been trained to protect the kingdom against.

Nimona’s got everything you could ever want in a “Kids’ movie”: Harrowing adventure, hateful betrayal, beautiful Achillean and Sapphic representation, heartbreaking social commentary, and, of course, a deliciously overt allegory for being transgender in a world that just can’t seem to wrap it’s mind around the concept. At least, until it’s forced to.

Nimona is based on the comic of the same name, which was created by the writer behind She-Ra and the Princesses of Power, Nate Stevenson: a transgender individual. The movie feels like it was written by Trans, Non-binary, and Gender Non-Conforming people, with the same people set as the target audience. It is so beautiful to see characters like Nimona given depth and miles of personality, on top of their gender identities.

So if you haven’t seen Nimona, I hope I’ve given you enough reason to put it alongside all the other worthwhile watches of the year.

For more information, check out the IMDB page: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt19500164/?ref_=ttmi_tt

Trigger warnings:

Analogies for transphobia

Mentions of suicide and a non graphic suicide attempt

Mild violence