Last fall, I took the Olin class Creativity Practicum, a studio class about understanding and finding your own voice in art and design. One of the first assignments has you watch a video titled “I Could Do That” by the YouTube channel The Art Assignment. The video talks about why people who look at art, such as a Pollock painting, and say something along the lines of “that’s not art, I could do that” should really think before they speak, but that’s not relevant to this Frankly Speaking piece–no, I mention the video because for approximately two seconds, a piece of art was splashed across the screen, and it completely changed the way I approach art.

But before we get to that, a little bit about me: I’ve been drawing since I could pick up a crayon. Art-making has been a part of how I express myself, reflect, and tell stories for my entire life. In high school, I made art like this:

Extremely detailed, highly accurate observational work. And I loved it! The process of observational drawing was (and still is) extremely meditative for me, and I’d sometimes become so absorbed in the process that I’d stand for four or five hours straight. However, I didn’t work quickly. A single piece would take me weeks or even months to finish.

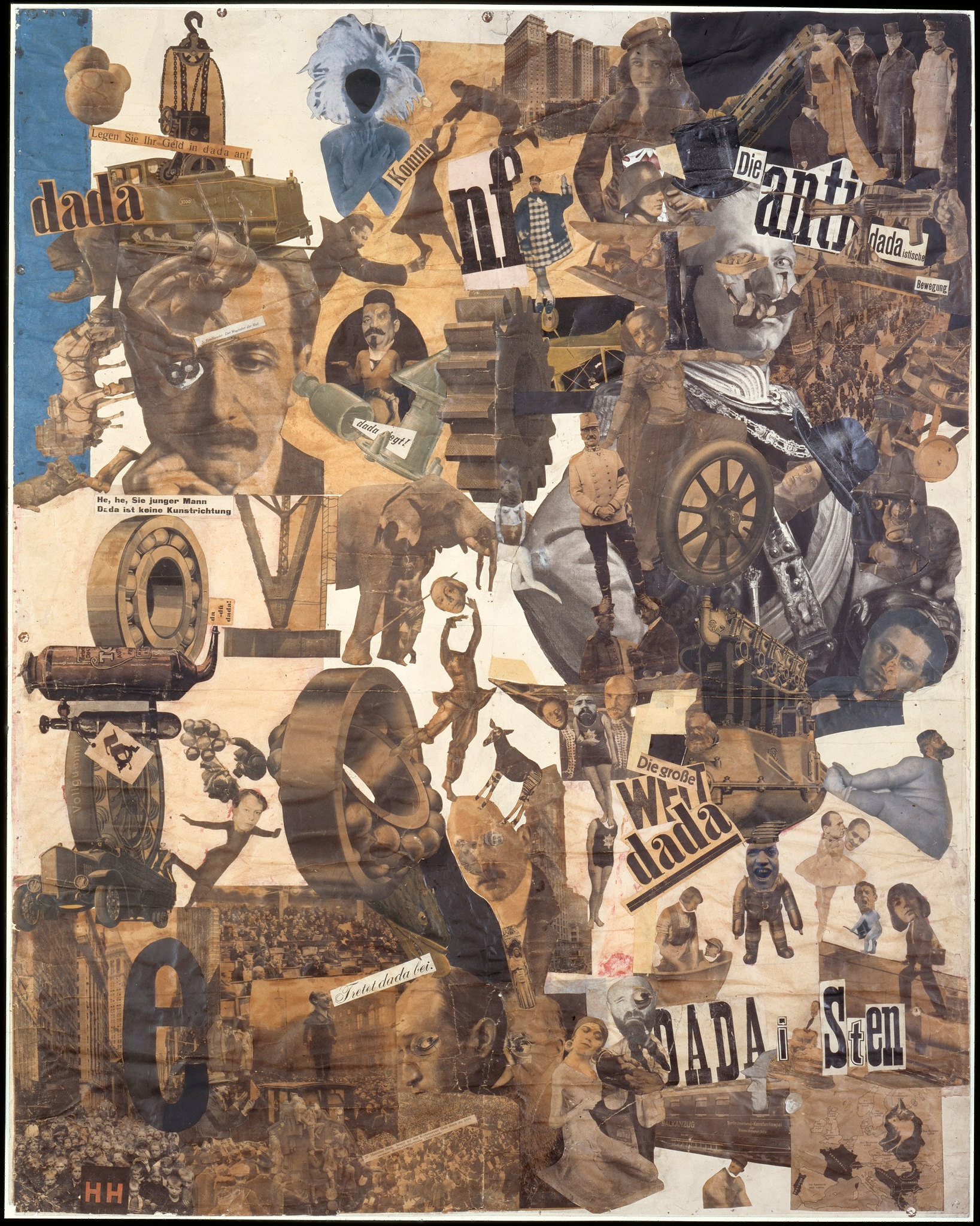

Creativity Practicum, on the other hand, pushes you to work fast. There isn’t any emphasis on the quality of work you put out, or even on the idea that you’re “making art” at all. Each week you explore a different idea–sometimes a specific artist’s work, sometimes a more abstract concept–and then on one page of a spread you’d put images you associated with the week’s assignment, and on the other, you’d create a summarizing image and write a half-page reflection. I went about completing the first assignment in the way I usually do, and inevitably didn’t finish, but didn’t think much of it because I didn’t need to have a finished piece. And then I watched the aforementioned YouTube video, which features this collage by Hannah Hoch:

The title is Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany. Concise… but I was captivated by it. I love how the crowded composition makes your eye dart around the picture, and how carefully cut out and placed each individual part is (such as the man juggling his own head near the center of the image, which, upon closer inspection, seems not to be his own head). I love that it’s disturbing and funny in the same breath. And, ironically, I love that whenever I look at it I think, “Wait a minute–I could do that!”

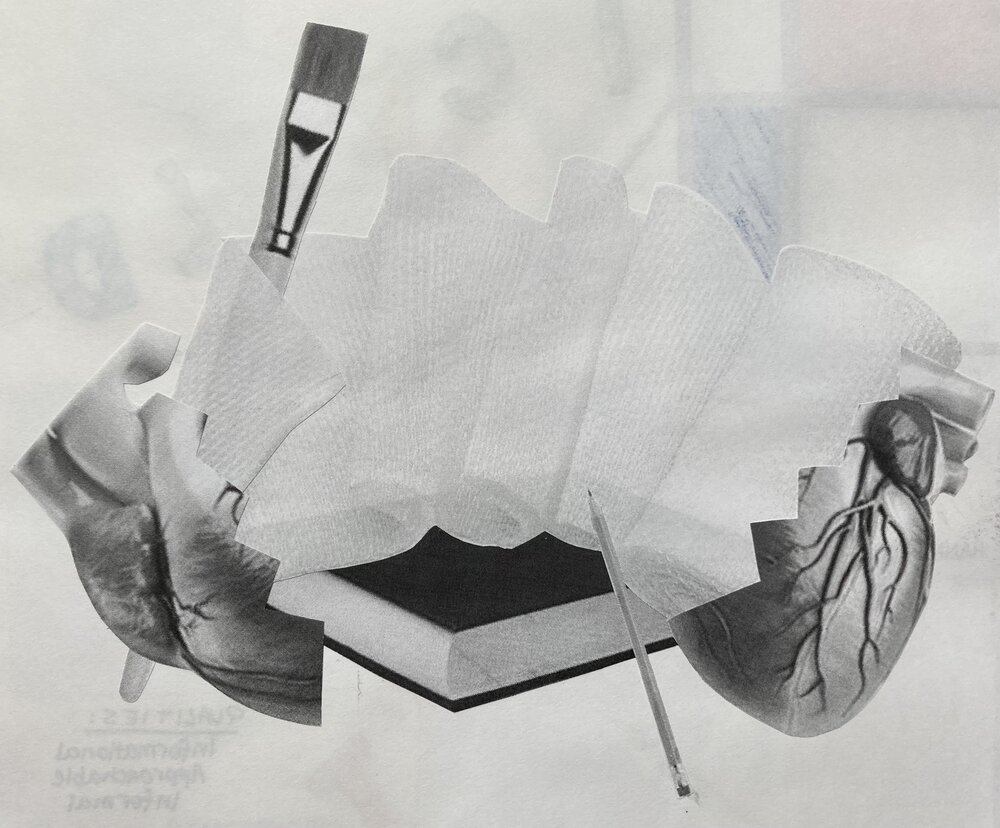

I was already thinking about the different images that came to mind for each assignment and taking note of them. What if instead of putting all this time and energy into a piece I crafted by hand, I simply took those images and arranged them in concert (or in chaos) with each other? I tried it out:

Okay, this was cool. Only one problem: the pages of my sketchbook were curling from all the glue. Then I remembered a girl in one of my high school art classes showing off some of the pages she’d made in Keri Smith’s Wreck This Journal, an interactive workbook that asks you to–well–I’ll let you figure it out. Her pages were wrinkled and torn and the notebook didn’t even close, but the pages inside were incredible. So I made the conscious decision to actively destroy every single page I worked on.

Throughout the semester, my art improved tenfold. Not only that, but instead of making one piece in four months, I made thirty. Less than half of them are things I’m proud of, and almost none of them are portfolio-worthy, but for the first time, I felt like I was conveying complex ideas and showing my personality through my work.

At home in the pandemic, I was constantly in the company of my childhood pet, Hobbes. His relentless affection was mostly reciprocated, but I sometimes felt he was a bit… needy. One day for fun, I made this:

Hobbes began to feature prominently in my work. Everyone in the class became familiar with him, and not just because whenever I unmuted they could hear distant meowing. For the class’s final project, a collection of postcards, I decided that each one would feature Hobbes among images from photographs I’d taken. And throughout the whole process, my mind kept returning to the collages of Hannah Hoch.

Hoch was part of the Dada art movement, which developed in Europe and New York in direct response to World War I. Hoch’s work specifically centered around identity construction–what does it mean to be a “modern woman” in the aftermath of such a devastating event? During the pandemic–which hasn’t ended!–I felt comfort in the way that Dada embraced nonsense. Nothing else in the world made sense, after all–why should our art?

Although we’re back at Olin, things still don’t feel “normal,” and there’s no promise they ever will be. But I can continue to grow, as an artist and a person, in spite of that. And I’m glad to have found my “mews.”